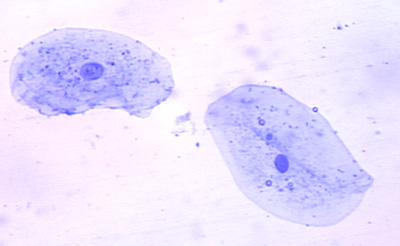

If you take a cotton swab and scrape it along the inside of your cheek, you can dab the soggy end onto a glass slide, put a drop of blue stain on it and, under a microscope, see the very building blocks of what you are. The average person is pretty unlikely to get hold of a microscope. So in some ways, you’ll have to take what I write here on the basis of some kind of authority, safe in the knowledge that you can test it yourself, at least in principle. Let’s imagine you’ve done it so. What you’ll see down that eyepiece will look something like the picture I’ve provided, a strange blob with a distinctive dark dot somewhere inside it.

This is one of your cheek cells. Cells are the units that make up our bodies. Each of us is composed of about 100 trillion of these units. That’s means that there are about 10,000 times more cells in your body than there are people in the world. Break down those cells into their component parts and you get the same stuff that everything around us is made of. Loads of water firstly. Then carbon, which we see in diamonds and in the black stuff in pencils. There’s also loads of oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen and even metals such as iron. These are quite literally the very same substances which make up the atmosphere, landscape and the everyday objects we see around us. The iron in your frying pan is no different to the iron in your blood. One is a solid lump; the other is in tiny microscopic pieces.

This is one of your cheek cells. Cells are the units that make up our bodies. Each of us is composed of about 100 trillion of these units. That’s means that there are about 10,000 times more cells in your body than there are people in the world. Break down those cells into their component parts and you get the same stuff that everything around us is made of. Loads of water firstly. Then carbon, which we see in diamonds and in the black stuff in pencils. There’s also loads of oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen and even metals such as iron. These are quite literally the very same substances which make up the atmosphere, landscape and the everyday objects we see around us. The iron in your frying pan is no different to the iron in your blood. One is a solid lump; the other is in tiny microscopic pieces.The DNA Blueprint

Cells are themselves very complicated structures, though we can’t see much detail through our microscope. They come together to form the structures of our body. Our muscles formed from muscle cells, our skin from skin cells, even our bones are formed from cells which eventually become solidified. It’s hard for many people to imagine how all of this non-living stuff can come together to form a person. The secret to all of this lies in that dark dot inside the cell. We’re going to need a bigger microscope.

That blob is called the nucleus. We can imagine it as being the brain of the cell, though of course it is not aware of itself in any way. If we tease the nucleus open and look inside, we get lots of protein and water. And we get 46 strange little bundles of carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen and oxygen. These are our chromosomes, within which the carbon and its friends are combined to make that most fabled of compounds; DNA. That stands for deoxyribonucleic acid. I’m not even 100% sure what that means incidentally, but trust me we’ll get by.

If we could somehow take a hold of one of those chromosomes and tug it apart, we’d find that this DNA isn’t a blob at all, but a single long string wound around itself and bundled up countless times. And if we look closer still, we find that the strand is composed of repeating patterns. Each unit of that pattern is called a nucleotide. There are four different nucleotides and each is given a letter to represent it. a, c, t and g. When we read off a given bit of our DNA, we can write it down something like this:

acactcgcttctggaacgtctgaggttatcaataagctcctagtccagacgccatgggt

Imagine that going on for roughly another three billion letters, that’s how long human DNA is, if you count all 46 chromosomes. Looking at that all day will really make your eyes sore. I have great admiration for those patient, or perhaps mildly crazy geneticists.

What does this pattern of letters actually mean? It’s a blueprint for you. The pattern is identical inside the nucleus of every cell in your body. After all, your cells were all copied from that one first cell created when you were conceived. Whether it’s in a muscle cell or a cheek cell, all that changes is which bits of the blueprint the cell reads. The way it reads them is really quite ingenious too.

The Code

Our DNA directs the way we are built. If we take cells from just one part of our body, we’ll find that they have exactly the same DNA code as every other cell, down to the last letter. But unlike the others, the cells usually use or “express” a part of that code which the others ignore. Some parts of the code are used by every cell we have, but many are unique to some part of us. When a piece of DNA is expressed, the cell makes a copy of that piece out of a similar substance called RNA. RNA too is a strand composed of four letters, but is only a copy of the specific part of the DNA that this cell is interested in. Once it is made, the RNA “message” travels right out of the nucleus of the cell and is captured by tiny structures floating around outside. The RNA message is spooled through these structures which read the message and spool out a protein. Proteins, just like DNA, are long strands. However, proteins are made up of an entirely different set of letters to our DNA. There are 20 protein letters, and although they look a lot like DNA letters, they’re quite distinct. A protein sequence looks a bit like this when we write it out:

MVHLTPEEKSAVTALWGKVNVDEVGGEALGRLLVVYPWTQRFFESFGDLSTPDAVMGN

It looks meaningless, but it is a translation of the message sent by our DNA. The message is read in groups of three letters. Every three RNA letters corresponds to one of the 20 protein letters. So for example, the message “aag” gives us a K. “agc” gives us an S. It’s a code.

As the new protein created, it starts to wind up, tangle, knot and generally form a blob, but with a shape that is the same every time that same protein is made. This is because, as well as sticking together end-to-end in a line, some of the protein letters also like to stick together sideways. What happens next depends on what protein has just been built. Keratin, for example is one of the proteins unique to our hair follicle cells and our nails. To make hair, the keratin protein is moved to the outside of the cell where it begins to harden. DNA is transcribed to RNA messages. RNA messages are translated into proteins. And proteins can do almost anything. Some, like keratin, are exported from the cell where they may serve to build structures or alternatively to send signals to other cells. Others, called enzymes, make new substances themselves such as fats and sugars. Still others stick around inside the cell to help the cell function, perhaps building new parts for the cell or deciding which pieces of the DNA code the cell will express and when. Some proteins will even add metals to themselves. Iron, for example, makes up a part of the haemoglobin protein in blood, capturing oxygen to bring it all around our body.

Any part of our DNA which codes for a protein is called a gene. Some are expressed constantly, others in response to information and, as I said before, many will only express when the cell is in the correct part of our body. So muscle cells make strong muscle fibres, our eye cells make amazing proteins that can detect light and our immune cells make lethal poisons to kill invaders. We each have over 40,000 genes, but because of the ways that the genes can interact with each other through the actions of proteins, the actual number of proteins those 40,000 genes can make is much, much greater. Since many of those proteins can combine together or make new substances, it’s easy to see where our complexity comes from. And all of this comes from that one identical blueprint, at the core of every cell, expressed in different ways. Of course what you are is also modified by your environment. Diet, exercise and countless other influences change your body. Memories reshape your brain. That’s really a whole other story. But it all starts with the code. It’s pretty astounding what each of us can do with just four letters.

6 comments:

so if we are what we code whats the difference in us one second prior to death (whilst alive) and one second post (brain) death?

We are energetic beings inhabited a body coded for but updated by the nervous system and its innate intelligence.

Thanks

Well, what constitutes death is still very much a matter of debate in medicine. In terms of the genetic code, nothing really changes within our cells at the moment of death. The cells are deprived of oxygen and begin to break down, but this is not instantaneous.

As to us being "energetic beings", it's a nice notion but not supported by any observations at this time. I'm not sure what you mean by our bodies being "updated" by our nervous system, nor what it's innate intelligence would be.

Of course it is supported by observation - what sort of "scientist" are you? The body weighs the same before and after death in fact just before degradation there is no difference between a live body and a dead companion other than the presence of an intelligent energy.

Innate intelligence describes the body's ability to maintain homeostasis and salutogenesis in the presence of ever changing needs and environments.

The nervous system animates the body and carrying information about its internal and external environments updates this inbuilt intelligence.

Without a nervous system to provide this, the body is nothing more than an organ bank.

DNA provides a plan for structure building and provision of material. It is unable to do this alone and thus is the mystery ignored by many – what directs their expression: the creation of protein, the transcription of RNA…

Thanks

"Of course it is supported by observation - what sort of "scientist" are you? The body weighs the same before and after death in fact just before degradation there is no difference between a live body and a dead companion other than the presence of an intelligent energy."

How do we measure this intelligent energy?

"Innate intelligence describes the body's ability to maintain homeostasis and salutogenesis in the presence of ever changing needs and environments."

Well homeostasis is a concept that I am quite familiar with, but I've rarely heard it referred to as "innate intelligence". As far as I am aware, innate intelligence is a concept from chiropractic. It is not a concept considered particularly meaningful by scientists.

"The nervous system animates the body and carrying information about its internal and external environments updates this inbuilt intelligence."

The cells that make up that system are coded for by our genome. The receptors which receive the internal and external information are coded. The signals sent out in response are coded. This is all quite well mapped out. What you seem to be describing is a quality that is emergent from this complex system.

"Without a nervous system to provide this, the body is nothing more than an organ bank."

I'm not disputing that.

"DNA provides a plan for structure building and provision of material. It is unable to do this alone and thus is the mystery ignored by many – what directs their expression: the creation of protein, the transcription of RNA…"

I'm sorry, but there really is little mystery to the above. Biologists understand very well how the body self-constructs, how organs differentiate and how protein expression changes in response to stimuli. They understand how this is directed. It can all ultimately be reduced to gene expression.

“How do we measure this intelligent energy?”

It cannot be measured but observed. Health, robustness, performance, resilience, and in its simplest form; adaptability.

“Well homeostasis is a concept that I am quite familiar with, but I've rarely heard it referred to as "innate intelligence". As far as I am aware, innate intelligence is a concept from chiropractic. (?) It is not a concept considered particularly meaningful by scientists.”

Scientist do not think homeostasis, the intelligent ability of the body to respond to its environment, internal and external; its maintenance and stimulation is not meaningful?

Chiropractic I am not overly familiar with but I think you should check out people like Bruce Lipton who use the term frequently during lectures and writing. It is also used throughout scientific journal as is the term innate ability and capacity of biological systems.

‘The nervous system animates the body and carrying information about its internal and external environments updates this inbuilt intelligence.’

“The cells that make up that system are coded for by our genome.”

Yes and indeed the nervous system is the first organ of the body to be created off which all other organs bud.

“The receptors which receive the internal and external information are coded. The signals sent out in response are coded. This is all quite well mapped out. What you seem to be describing is a quality that is emergent from this complex system.”

Correct and incorrect. What you are describing is its language and carriers not the seemingly intelligent ability of the body in adapting to its environment striving to survive and thrive. It is not emergent but inherent.

"It can all ultimately be reduced to gene expression."

Gene expression by whom or what? This is like saying music can be reduced to the expression of a piano and its keys. Yes indeed it can but by whom or what is what I am asking you consider and which and I don’t mean to be rude here but you don't appear to comprehend.

“(Intelligent energy) cannot be measured but observed. Health, robustness, performance, resilience, and in its simplest form; adaptability.”

That’s quite a nebulous definition. I have no doubt that a great many factors influence gene expression, but unless you can observe and quantify this “intelligent energy” then it does not have much of a place in our discussion.

“Scientist do not think homeostasis, the intelligent ability of the body to respond to its environment, internal and external; its maintenance and stimulation is not meaningful?”

I didn’t say that, I said that “innate intelligence” is not a concept that is considered meaningful by biologists. Homeostasis is well understood of course.

“Chiropractic I am not overly familiar with but I think you should check out people like Bruce Lipton who use the term frequently during lectures and writing. It is also used throughout scientific journal as is the term innate ability and capacity of biological systems.”

I’m not familiar with Bruce Lipton’s work but I understand he’s a writer in the field of meta medicine. Deepak Chopra style stuff. I have to stress that this work is not widely accepted by scientists or by the medical community. A detailed debate of that issue is probably beyond us here.

“Yes and indeed the nervous system is the first organ of the body to be created off which all other organs bud.”

Yes, the neural tube is the first identifiable organ that develops in vertebrate embryos. Its development is based on genes expressed in response to local soluble factor concentration gradients. Those gradients are themselves caused by gene expression based upon simpler axial gradients and so on. The starting point is a simple apical/basal axis in the zygote cell. Increasingly complex layers of expression are built up over that starting axis. Essentially a grid, defined by gene expression patterns, which further defines tissue differentiation. The nervous system certainly becomes involved once it has formed, but so do many other systems (for example, the chemokine system). The nervous system is not really the controlling or initiating element of embryogenesis.

To learn more I would recommend a review paper covering vertebrate embryogenesis. The topic is certainly too complex for me to address here.

“Correct and incorrect. What you are describing is its language and carriers not the seemingly intelligent ability of the body in adapting to its environment striving to survive and thrive. It is not emergent but inherent.”

We can explain this fully in terms of gene expression. Unless you can show that to be incorrect, there’s not much call for assuming that what you are describing is anything more than a large scale effect of genetics interacting with environment. Certainly the use of less complex, large scale models has value, since describing large systems entirely in terms of the underlying genes is extremely awkward.

“Gene expression by whom or what? This is like saying music can be reduced to the expression of a piano and its keys. Yes indeed it can but by whom or what is what I am asking you consider and which and I don’t mean to be rude here but you don't appear to comprehend.”

To draw an analogy between something created by a person and something that arises naturalistically is immediately going to lead you into some confusion. A piece of music must be written by a person. Further, it has no meaning unless heard and understood by a person. By contrast, gene expression is either self controlled or controlled by other genes. No second party, no “whom” is needed. It is a complex network, but genes are not servants to any larger structures in the body. Quite the opposite.

I would highly recommend Dawkins’ book The Selfish Gene for a comprehensive explanation of how genes direct life.

Thank you for posting.

Post a Comment